Why India Must Invest More in Higher Education Research

Why India Must Invest More in Higher Education Research

Introduction

India’s higher education system, with over 58,000 institutions and 43.3 million students enrolled in 2021-22, is the world’s second-largest, yet it faces a critical challenge: underinvestment in research and development (R&D). India allocates only 0.65% of its GDP to R&D in higher education, lagging behind global leaders like the United States (2.8%), China (2.1%), and Israel (4.3%) [World Bank]. This underfunding constrains research infrastructure, limits faculty recruitment, and weakens India’s global academic standing, despite its fourth-place ranking in publication volume. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 envisions a Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) of 50% by 2035 and aims to position India as a knowledge hub, necessitating substantial investment in research. Scholars have long emphasized the link between higher education investment, socio-economic development, and human capital formation. This article argues for increased funding in higher education research, correlating it with rising enrolment and faculty shortages in central and state universities, to support NEP 2020’s transformative goals.

India’s Higher Education: A Rising Global Leader

Key Impacts of NEP 2020 on Higher Education

Gross Enrollment Ratio in Indian Higher Education: NEP 2020 Targets vs. Current Reality

Review of Higher Education Research Investment in India

Current State of Investment and Enrolment Trends

India’s public expenditure on education is approximately 3% to 4% of GDP, with higher education receiving a small fraction. The Union Budget 2025-26 allocated INR 1.28 trillion to education, a 6.5% increase from INR 1.20 trillion in 2024-25, reflecting a 51.33% rise since FY19 [Business Standard]. However, R&D expenditure remains stagnant at 0.6–0.7% of GDP, far below South Korea (4.2%) or Israel (4.3%). The All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021-22 reports 43.3 million students enrolled, up from 41.3 million in 2020-21, with a GER of 28.4% [AISHE]. This growth, driven by undergraduate (78.9%) and postgraduate (12.1%) programs, underscores the need for investment to match rising demand. Tilak (2005) argues that higher education catalyses economic growth by developing human capital, yet India’s low investment limits this potential [Varghese & Panigrahi, 2019].

The Union Budget 2024 introduced loans up to INR 10 lakh for higher education, benefiting one lakh students annually, reflecting demand for accessible education. However, without increased R&D funding, universities struggle to support advanced research, particularly at the PhD level, where only 0.5% of students are enrolled [AISHE].

Faculty Shortages and Their Impact

Faculty shortages are a significant barrier, exacerbated by low investment. As of 2020, central universities in states like Haryana and Bihar operated with only 52% of sanctioned faculty positions filled [Drishti IAS]. State universities face similar challenges, with budgetary constraints hindering recruitment. India’s pupil-to-teacher ratio is 30:1, compared to 12.5:1 in the USA and 19:1 in China, impacting research mentorship and teaching quality. Varghese (2019) highlights that faculty shortages in public universities limit research output and institutional capacity [Varghese & Panigrahi, 2019]. Increased investment could fund competitive salaries and research grants, addressing the 40% vacancy rates in central and state universities and supporting NEP 2020’s multidisciplinary goals.

Challenges of Privatization and Commercialization

The rise of private universities (361 of India’s 1,000+ universities in 2020) has expanded access but prioritized profit over research [Wikipedia]. Private unaided colleges account for 65.2% of enrolment, compared to 21.5% in government colleges, yet their focus on revenue limits R&D investment [Varghese & Panigrahi, 2019]. Tilak (2006) critiques the centralization of education funding, arguing it exacerbates regional disparities and underfunds public institutions [Tilak, 2006]. The Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA) aims to mobilize INR 1,00,000 crore for infrastructure, but research funding remains inadequate, burdening students with loans and increasing financial stress on families.

Global Competitiveness and NEP 2020

NEP 2020 targets a 50% GER by 2035 and aims to establish India as a global research hub. However, only three Indian institutions – IIT Bombay, IIT Delhi, and IISc Bangalore – ranked in the top 200 of the QS World University Rankings 2020, reflecting limited global competitiveness [PIB]. India has 1,200 researchers per million population, compared to 7,100 in South Korea, constraining research output [IMARC Group]. Tilak (2005) emphasizes that higher education investment is critical for socio-economic development, yet India’s low R&D spending hinders innovation [Tilak, 2005]. Programs like the Global Initiative of Academic Networks (GIAN) and Study in India require robust funding to attract international talent and reduce the outflow of about 500,000 Indian students studying abroad annually [Study in India].

Expenditure Trends

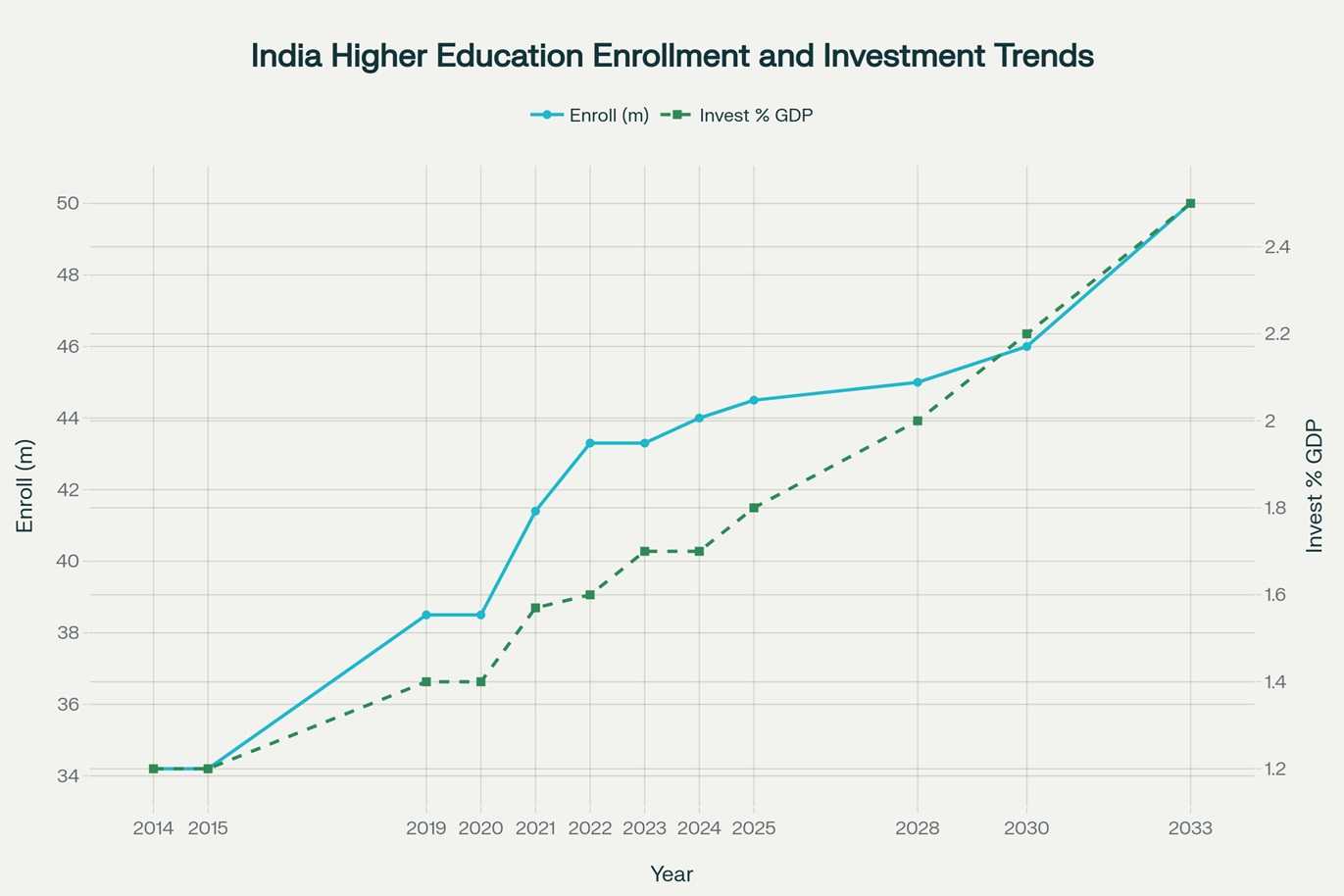

The following table and charts illustrate India’s higher education expenditure trends and their correlation with enrolment growth.

| Year | Expenditure (INR Million) | % of GDP | Enrolment (Million) | GER (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 500,889 | 1.09 | 14.6 | 12.4 |

| 2010 | 977,367 | 1.34 | 18.6 | 15.0 |

| 2016 | 1,200,000 | 1.20 | 35.7 | 25.2 |

| 2021 | 1,200,000 | 0.90 | 41.3 | 27.3 |

| 2022 | 1,280,000 | 0.85 | 43.3 | 28.4 |

Sources: AISHE 2021-22, Ministry of Education, World Bank Data

Chart 1: Public Expenditure on Higher Education (% of GDP): 2007 to 2022

Chart 2: Enrolment vs. Expenditure Trends: 2007 to 2022

Analysis

The data highlights a critical mismatch: enrolment has nearly tripled since 2007, but public expenditure as a percentage of GDP has declined, straining resources. Faculty shortages, with over 40% vacancies in central and state universities, hinder research and teaching quality. Varghese (2019) notes that private institutions, despite higher enrolment, contribute minimally to research due to their commercial focus [Varghese & Panigrahi, 2019]. Tilak (2006) advocates for increased public funding to address regional disparities and enhance research capacity [Tilak, 2006]. Investment in research infrastructure and faculty recruitment could elevate India’s global academic standing, reduce brain drain, and align with NEP 2020’s vision.

Concluding Observations

India’s higher education system requires urgent investment to strengthen its research ecosystem. Rising enrolment and persistent faculty shortages in central and state universities underscore the need for increased R&D funding, ideally to 2% of GDP. Tilak and Varghese emphasize that higher education investment drives socio-economic progress and human capital development, critical for India’s goal of a USD 10 trillion economy by 2035. NEP 2020 provides a transformative framework, but its success depends on robust financial commitment. Policymakers must prioritize research-focused universities, streamline faculty recruitment, and foster industry-academia partnerships to position India as a global knowledge hub. Failure to act risks squandering India’s demographic dividend and perpetuating inequities. The time for bold investment and commitment to strengthen State universities is now.

- All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021-22. Ministry of Education, Government of India.

- National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. Ministry of Education, Government of India.

- Budget 2025: India’s Education Budget Grows. Business Standard, 2025.

- Higher Education in India: Challenges and Opportunities. Drishti IAS, 2019.

- India Higher Education Market Statistics & Analysis, 2033. IMARC Group.

- Public Expenditure on Higher Education in India. ResearchGate.

- India’s Higher Education from Tradition to Transformation. PIB, 2025.

- Tilak, J.B.G. (2005). “Higher Education and Development. Journal of Higher Education.

- Tilak, J.B.G. (2006). “Education: A Saga of Spectacular Achievements and Conspicuous Failures. India: Social Development Report.

- Varghese, N.V., & Panigrahi, J. (2019). “India Higher Education Report 2018: Financing of Higher Education.” SAGE Publications.

- Higher Education in India. Wikipedia, 2024.

- Study in India Program. Government of India, 2020.

- World Bank Data. R&D Expenditure (% of GDP).